|

Incentives and Health Promotion: What Do the Data Really Say?

For a comprehensive review of research showing that rewards in general tend to diminish intrinsic interest as well as quality of performance, please see Punished by Rewards. The two specific issues on which most research in the field of health promotion has been conducted are effects on smoking cessation and weight loss.

SMOKING Research reviews 1. Dyann M. Matson et al., “The Impact of Incentives and Competitions on Participation and Quit Rates in Worksite Smoking Cessation Programs,” American Journal of Health Promotion 7 (1993): 270-80, 295. * Reviewed all available research from 1960s through early 1990s * Most studies found to be of very poor quality: of 30, only 8 had “an appropriate comparison group which allowed separation of the effects of incentives and competition from other program elements.” And only 3 looked at effects after 12 months or more. * Of 8 studies with an appropriate comparison group, only 3 even found greater participation in the program as a result of incentives. And “the research did not show incentives & competition enhancing long-term quit rates past 6 months.” 2. Pat Redmond et al., Can Incentives for Healthy Behavior Improve Health and Hold Down Medicaid Costs?, Center on Budget & Policy Priorities, June 2007: “Published research does not support the idea that financial incentives are effective at getting people to stop smoking. Although financial rewards may prompt people to use self-help materials or even to quit for a short time, no research has shown that financial rewards produce improvement in the number of people who succeed in quitting smoking entirely.” 3. K. Cahill and R. Perera, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2008, issue 3): * Looked for all rigorous controlled studies and found 17. * “None of the studies demonstrated significantly higher quit rates for the incentives group than for the control group beyond the six-month assessment.. . . Smokers may quit while they take part in a competition or receive rewards for quitting, but do no better than unassisted quitters once the rewards stop.”

Most recent study Press accounts of a Philadelphia Veterans Administration study (Kevin G. Volpp et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Financial Incentives for Smoking Cessation,” New England Journal of Medicine, February 12, 2009, vol. 360: 699-709) claimed that a positive effect from incentives had finally been found. But a careful reading of the study itself reveals: * the study didn’t evaluate any non-incentive interventions. Participants either received an incentive for quitting or were in the control group and received no help at all; * the “primary endpoint” for judging the effect was at 12 months even though rewards were still being paid at that point. (What matters is how people fare after the rewards have stopped); * at 15 or 18 months, the quit rate for those receiving incentives was greater than for those in the control group but was still extremely low in absolute terms: below 10 percent; * for those in the incentive group who did manage to quit after 9 or 12 months, about one out of three subjects started smoking again once another 6 months had passed. That relapse rate was actually higher than for those in the control group.

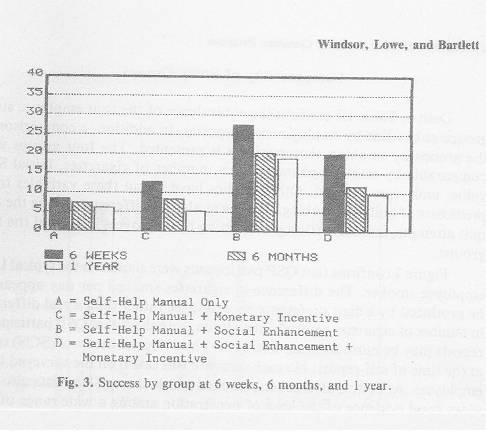

Better studies What about studies that offered various types of intervention to help people quit so that the effect of an incentive could be evaluated in conjunction with these cessation programs? 1. Dyann Matson Koffman et al., “The Impact of Including Incentives and Competition in a Workplace Smoking Cessation Program on Quit Rates,” American Journal of Health Promotion 13 (1998): 105-11: * A very large study at three worksites that featured a multicomponent program (self-help package + small-group support + monthly phone counseling) -- with and without incentives. These incentives “were much larger and were provided over a longer period than in other controlled studies.” Also evaluated: a contest between groups to see which had the best quit rate. Effects were evaluated at 12 months. * Results: (a) no significant benefit from the incentive; (b) anecdotally, the contest was particularly counterproductive; and (c) in discussing what did seem to help, “counselors emphasized self-control and confidence building so that participants did not attribute their cessation to external factors such as incentives” – meaning that an effort had to be made to try to counteract the negative effects of using rewards. 2. Richard A. Windsor et al., “The Effectiveness of a Worksite Self-Help Smoking Cessation Program: A Randomized Trial,” Journal of Behavioral Medicine 11 (1988): 407-21: * Random assignment to four conditions featuring various combinations of different interventions: a self-help manual; skill training and “social enhancement”; and an incentive. Effects were evaluated at 12 months. * Result: the incentive not only didn’t help but reduced the effectiveness of other strategies.

3. Susan J. Curry et al., “Evaluation of Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation Interventions with a Self-Help Smoking Cessation Program,” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 59 (1991): 318-24: * 4 conditions: personalized feedback (highlighting intrinsic reasons for quitting based on people’s questionnaire responses), an incentive, both, and neither (control group). * Results: incentive recipients were more likely to return the first progress report, but had worse long-term results than those who got the feedback with no incentive – and also did worse than those in the control group. Incentive recipients had higher relapse rates than those in the feedback or control group and were twice as likely to lie about quitting.

WEIGHT LOSS Research review National Business Group on Health’s Institute on the Costs and Health Effects of Obesity, “Financial Incentives -- Summary of the Current Evidence Base: What (and How) Incentives Work,” 2007: Despite an obvious pro-incentive bias (the stated purpose of the report being to advise companies on how, not whether, to design incentive plans), the authors conclude with apparent reluctance that rewards at best can increase participation rates in a program and boost short-term compliance, but the evidence finds “no lasting effect” on weight loss (or smoking cessation).

Early studies 1. Richard A. Dienstbier and Gary K. Leak, “Overjustification and Weight Loss: The Effects of Monetary Reward,” paper presented at annual convention of the American Psychological Association, 1976: * Very small study. Subjects weighed twice a week. Only two conditions: incentive and control group. * Incentive recipients made more progress at the beginning, but after incentives stopped, control subjects lost an average of 3.5 lbs, while incentive subjects gained 6.1 lbs. 2. F. Matthew Kramer et al., “Maintenance of Successful Weight Loss Over 1 Year,” Behavior Therapy 17 (1986): 295-301: At 12-month follow-up: “The principal hypothesis, that subjects entering into financial contracts for attending skills training sessions or for maintaining posttreatment weight would show better maintenance one year after successful weight loss than subjects receiving no maintenance support, was not confirmed.” The only significant difference: many incentive recipients failed to show up for the final weigh-in.

Most recent study A report from the same Philadelphia V.A. study mentioned above (Kevin G. Volpp et al., “Financial Incentive-Based Approaches for Weight Loss,” Journal of the American Medical Association, December 10, 2008, vol. 300: 2631-37) was, like the smoking cessation study, widely described as having demonstrated the effectiveness of incentives. However: * the study was very small (only 19 people in each condition, almost all of whom were men) and, again, did not evaluate any non-incentive interventions; subjects received only incentives or nothing; * only subjects in the reward condition were weighed daily, so any positive effect that might have been found could well be from the motivation of the expected weighing rather than from the reward; * news accounts mentioned early results favoring those who received incentives but failed to mention the bottom line: at the final follow-up, incentives provided no significant benefit.

|

||

|

Copyright © 2009 by Alfie Kohn. This article may be downloaded, reproduced, and distributed without permission as long as each copy includes this notice along with citation information (i.e., name of the periodical in which it originally appeared, date of publication, and author's name). Permission must be obtained in order to reprint this article in a published work or in order to offer it for sale in any form. Please write to the address indicated on the Contact Us page. |

||

|

www.alfiekohn.org -- © Alfie Kohn |

||